On January 10, the South African rand crashed about 9% in just a matter of minutes. It was the largest move for the currency since October 2008, an ominous yet poignant sign of just how bad everything was globally at that time. CNY had been pummeled up until the PBOC acted but a few days before. Even though the world was in the midst of turmoil, the incident was typically described as the collateral damage of prudent regulation combined with mystery. That is what QE has done to so many, fooling people into making excuses for what would otherwise be obvious.

Such flash crashes will probably become more common in foreign-exchange trading as liquidity shrinks amid tighter regulation and reduced demand for emerging-market assets, according to Insight Investment Management Ltd. and Citigroup Inc. [emphasis added]

If you actually listen to what is being said but from a more realistic approach not married by emotion to “stimulus” and “money printing”, the world’s big monetary problem is actually being described and in a reasonably open fashion. The trouble in terms of commentary is orthodox bias.

“The rand isn’t alone in this,” said Paul Lambert, London-based head of currencies at Insight Investment, a Bank of New York Mellon Corp. unit, which manages more than $582 billion. “The rand is another reflection of the change in the liquidity environment in which we’re all operating. We’re learning that unless there are clients on the other side, banks are very unwilling to take risk onto their books.” [emphasis added]

Here’s a separate Bloomberg article on the same subject of the January rand crash:

“The huge spike in risk aversion last week, poor liquidity and position liquidation have hit the rand,” said Robert Rennie, the global head of currency and commodity strategy at Westpac Banking Corp. in Sydney. The rand plunged to its all-time low shortly after midnight in Johannesburg. Data compiled by Bloomberg showed that offers to buy the rand against the dollar dried up around 7:04 a.m. Tokyo time.

What was the primary indication of “risk aversion” and “poor liquidity”?

China strengthened the yuan’s reference rate slightly for a second day on Monday after an eight-day run of reductions that sent shock waves through financial markets, while swings in local asset prices have revived concern about the government’s ability to manage an economy set to grow at the weakest pace since 1990.

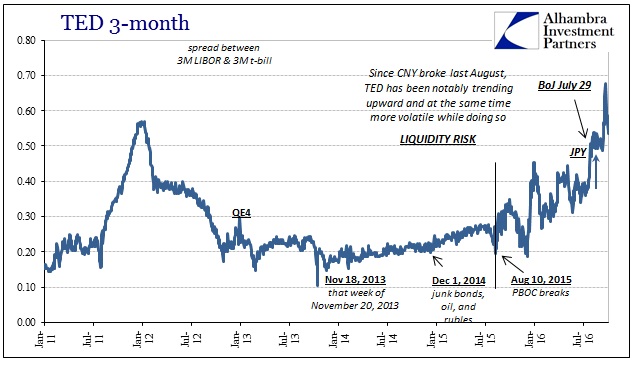

The mainstream narrative because of how it views QE always puts the cart before the horse, stringing these pieces together in a backwards manner. China didn’t “devalue” CNY sending “shock waves through financial markets” leading to low liquidity which left the rand particularly vulnerable because of South Africa’s economy (and high margin trading of Japanese retail investors, another excuse offered in the article), these “shock waves” were the result of banks “unwilling to take risk on their books” undercutting global “dollar” liquidity, causing the Chinese to bid at increasing premiums for “dollars” and leaving the rest of the world’s markets even more deprived of them as volatility becomes self-reinforcing.

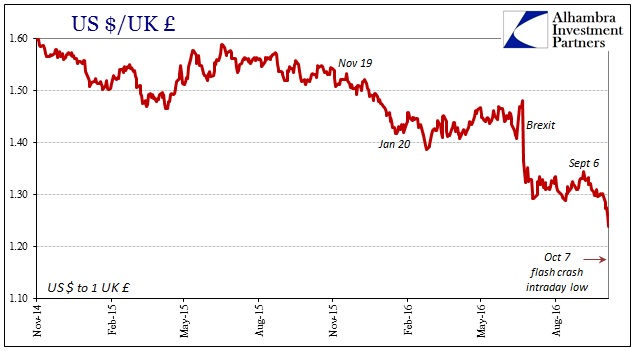

This episode is worth reviewing as a lesson in global wholesale conditions, but also as a template for recurrences; like today. The big news this morning wasn’t the lackluster payroll report, rather it was the flash crash of the UK pound. Though sterling isn’t nearly what it used to be as a co-reserve currency under Bretton Woods, it isn’t either some minor currency with little wholesale presence (no offense to South Africa).

Attention has immediately focused on Brexit and the uncertainties about how that might work, culminating in (what else?) regulatory-driven low levels of liquidity.

“This is not something you would expect in a half-efficient market,” said Ulrich Leuchtmann, head of currency strategy at Commerzbank AG in Frankfurt. “We have a liquidity situation which has eroded massively over the last few years and policy makers have largely ignored it. All the regulation that we have in place, for good reason, has the side-effect that liquidity in the FX market is much more shaky and fluctuating heavily, and we have times when it’s extremely low, especially in Asian trading.”

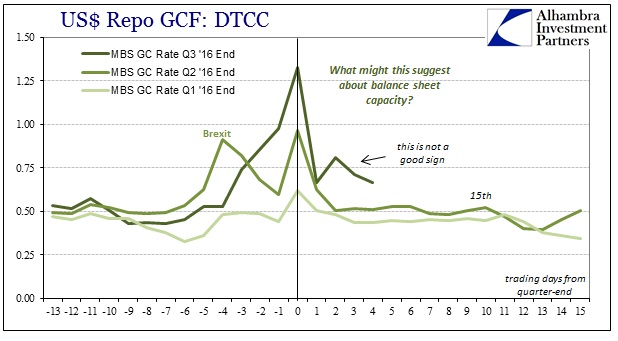

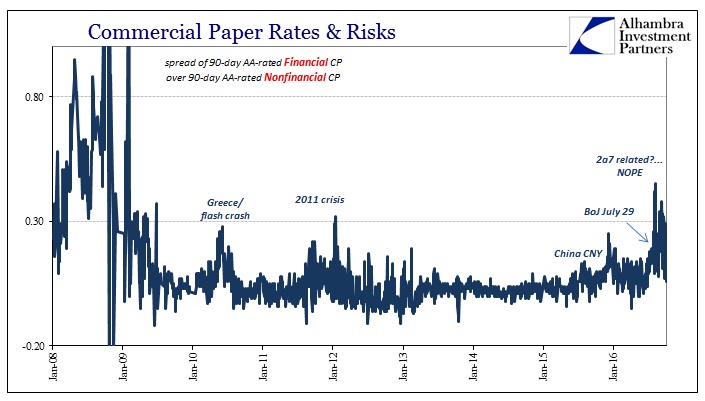

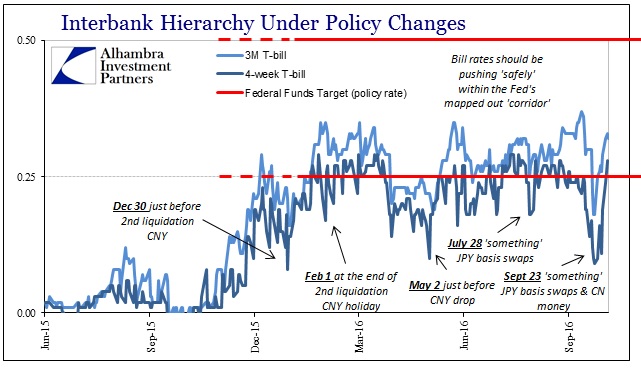

Regulation is a convenient and plausible (sounding) apology so as not to have to contradict established monetary principles no matter how many times they are disproved by action and empirical evidence. It’s not as if this has come out of nowhere, either. Brexit may have been some catalyst, but a flash crash in GBP is a big deal and once again speaks to the “dollar” shortage. As a reminder, there has been no shortage of indications about the treacherous state of global balance sheet capacity in recent weeks; starting once again with China’s connection to the eurodollar system and how that has affected its own RMB markets.

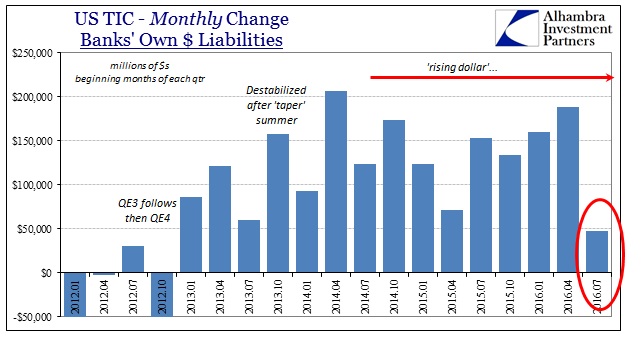

What is perhaps most interesting and relevant might be the timing – today in Asian trading when the Chinese presumably are completely missing because of their holiday. In other words, if the PBOC or its directives to state banks have been “supplying dollars” since especially August in order to keep CNY more stable above 6.685, then that might account for such drastically low liquidity that even the (still) mighty British pound might experience what was once reserved for banana republic currencies under more stable global monetary regimes. Without China’s efforts, there may be very little “dollars” on offer across Asia.

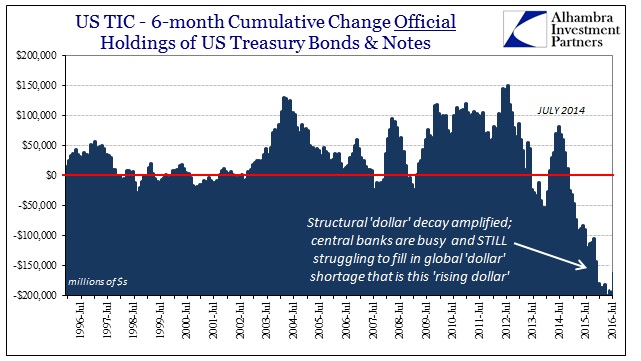

It is, I think, more (good?) evidence for what I suggested about central bank and official sector activity in their collective “selling UST’s”:

The private segment continues to buy on net while the official sector continues to sell on net. I think it fairly reasonable to conclude that the latter is purposefully designed so that the former can take place. In other words, global central banks (not just China) are attempting to intervene and calm “dollar” (funding) markets so that private entities (local banks and their “dollar short”) aren’t forced into hugely disruptive liquidations, able then to carry out the normal course of trade under the “dollar short.”

Subtract the PBOC doing exactly that this week and the result is a frightening crash for sterling? This is not regulations prudently pinching unbridled risk taking (still leaving unexplained the volatility in the first place), it is instead a growing “dollar” shortage whereby the global response to it has been ad hoc, unplanned, and carried out at best in uneven fashion. Staying faithful to QE means being stuck in the dark about practically everything.

To the mainstream, these are all just unrelated, random accidents on the road to recovery which just so happens to be left always just beyond the horizon. Because of so much “stimulus”, the financial system is resilient and the recovery assured. It’s a much more comfortable argument to make than to properly claim the “dollar” is a mess and only getting worse, and that is why not only has the recovery been stretched it is never coming at all so long as the global “dollar” remains in this very precarious state.

Stay In Touch