Erik: Joining me now is Professor Steve Keen, formerly a professor from a university in London. Now, professor at large teaching economics on the internet via Patreon. Steve, it's been way too long. It's great to have you back on the show. But you know, you have been one of the most outspoken guys talking about why too much debt really leads to a macroeconomic prognostication or diagnosis or forecast, whatever you want to call it of ongoing deflation.

My big question to you is, boy, it seems to me like the politics have changed and we maybe are back to the late 1960s and facing and incipient not just little whiff of inflation. But I think secular shift to a really big inflation, that's going to be a big deal. Am I crazy? What do you think?

Steve: Well we suddenly got a shock coming through from the supply side of things. I mean, COVID has obviously disturbed global production chains around the planet. We're seeing signs of that as well with climate change, with Taiwan running out of water and therefore not able to supply the chips to the world. So if you've got big increase in, you know, their essential, highly transformed manufacturing input. then you have a range of other commodities, I believe copper and nickel. The two that are showing signs of supply disruptions. So all this stuff meant you're going to get a supply kick, cost of production kick coming through. Which, you could actually like into what happened back in 1973-74, with The Yom Kippur War, the OPEC blockade, and the increase in oil prices from $2.50 a barrel to $10. And then the same in 1979-80, when they went from $10 to $40.

So definitely there's a price hit coming through from the supply side of the economy. But what is different this time around is that when that happened in the 70s. You had an absolute mother of all booms on, which was credit finance. And you also had unemployment so low. I mean, it was an insensitive recorded level in America is running at about of the order of 4%, 3% to 4%, which is comparable to what they are calling the unemployment numbers these days. But frankly, the numbers were more honest back then. There has been so much hiding of unemployment in the not looking for work section of the statistics I think you've pretty much got a double the unemployment rate to make it comparable to what was actually being properly recorded back in the 70s.

Steve: With the very tight labor market, and the booming credit conditions in the 70s. That meant that that supply shock was passed on to prices. So you had and this is where the endogenous money thinking comes in. You had a huge increase in the price of obviously oil. That was then covered by firms accessing their lines of credit to pay for it, which gave us stimulus courtesy of the cost goes into the economy as well. Workers were particularly when you had trade unions, which had been decimated in the last 40 years, 40 to 50 years. They could bargain for higher wages as well. So you got to flow on from the supply shock of the increase in the oil prices to an increase in wages. And you then had this income distributional battle, the wage price spiral, which went on for a while until it was crushed by the massive increase in interest rates on [inaudible]

Now, you don't have anything like the credit demand anymore, nor do you have the bargaining power of the working class. They've been destroyed. They were bad enough in the 70s. In terms of political power in America, they've been crushed in the last 40 years. So I don't think you're going to see the aggregate demand follow through to that supply shock. So I expect an increase in prices, quite a sharp one in particularly in raw material prices, and also CPUs. But then that will peter out because the demand won't be there. So I see the price hit, leading to a decline in the numbers being sold, rather than an increase in the money being borrowed to purchase those and keeping the price momentum going.

So if you look back at the 1970s, and take a look at the what the unemployment rate was before the crunch began in the oil price rise. In 1972, you had an unemployment rate of 6%, which fell to 4.6%. Next, that's a genuine recording of the unemployment rate. And at the same time, credit was running at about 11 and a half, 12% of GDP. Which was quite high. It's only been higher three times, four times pardon me. The fourth time being the beginning of the 2007 crash. Now, when you when you think from the point of view of capitalists and investors. When you have a huge increase in wage costs and raw materials, you have a drop in your profit margin. So the credit demand plunged from that point. It went from 12% of GDP down to five and a half percent. And that's when you had the huge rise in unemployment at that stage and you had inflation and unemployment. I think you're gonna have not a large downturn, but I just don't think the kick to inflation is going to be there.

Erik: Steve talk to me about the relationship between inflation and bond rates because I'm noticing a lot of investors acting as if inflation caused bond rates to increase. And I would argue it doesn't work that way. Inflation sometimes inspires central bankers to take actions which cause bond yields to increase. But I don't think the inflation is causing it. I think it's the inflation is inspiring the central bankers to make policy actions that do it. How is this relationship? How does it really work between inflation and bond yields?

Steve: Well, the point which endogenous money theory and the modern monetary theory as well, and this is stuff that central banks are confirming rather than denying. Points out is that the central bank can set any rate of interest at like fundamental ease. It's the Comptroller of the base rate of interest. It can't control the far end, it can't control long rates, but at the short rate end, it basically sets the price. And therefore it's determining. It's not a market driven system. It's the decisions of the central bank as to what that short term rate could be. And we saw Volker putting it up, you know from what 8% to 17% as a policy move to try to suppress the inflation back in the late 70s, early 80s. So it's a policy instrument at the shorthand. It's more market driven at the long end. But overall, in terms of certainly short term bond yields. If the central bank doesn't think the inflation that they're seeing is sustained, then they won't be putting up their short term rates, and you won't see a follow through from inflation to interest rates.

Erik: How would you interpret what's happened so far to the US 10 year Treasury yield? Because it seemed at first like people were really freaking out and afraid that it was running away and somehow we hit about 1.75 and all the sudden it seems to have just settled down. Are we done? Or are we just pausing before moving higher?

Steve: I can't, I just can't see it moving higher because I mean, the bond rates, if you're talking government bonds, and government can pay effectively any rate it wants to pay on the bonds. If it issues its own currency, it's you know, in effect the Treasury can borrow from the central bank and pay zero interest on that borrowing to pay the interest they then pass on to bondholders. So there's no mechanism to force the government's hand in that sense. And when you look at the level of debt that the private sector is carrying, there's no way I think the private sector can handle an interest rate, even near 1% higher than things are right now. Because the corporate sector in America right now is carrying the highest level of private debt compared to GDP in its history.

That's been co-driven by COVID of course. The giant spike in the level of private debt for corporations, which I think, I would expect it was being caused by having to, you know, access lines of credit and overdrafts to cope with the low cut of cash flow for from COVID. So just to give you those numbers, the corporate sectors, corporate sector, private debt, a debt-to-GDP ratio, when 2020 began was 75% of GDP. By September, it was 84% of GDP. That's almost a 10% jump in nine months. So that is not a corporate sector that can handle a large cost increase in its interest rate costs. So I just don't think we've got momentum for interest rates to go much higher.

Erik: Steve, let's come to the subject of modern monetary theory. You have expressed what I would describe as a proponent position. You like this idea of MMT. I personally have concerns with it. But I'll tell you, I'm convinced of one thing, which is whether I like it or not. It's happening. You've been following this for quite a while. How do you see what I think is really a political power change, all of a sudden the people who are in power are very friendly to what I would describe as maybe your monetary politics as opposed to my monetary politics. Now that your team's kind of got the power. How do you see this going down? What happens in terms of how these MMT concepts are adopted now that the people who have been supporting them seem to be in power?

Steve: Well, it's not so much people who support a policy is as saying that what MMT shows. It is simply using accounting to say what are the consequences of government debt? What are the consequences of government spending, and borrowing and so on. And it's realism about that, versus, you know, we're all going to be ruined stuff. If you read the macro textbooks of the mainstream people like Gregory Mankiw, who will argue the government debt first of all, if the government borrows money, or if the government increases its issuance of bonds, which is what it actually does, then that is going to take money out of the Private Sector so more government borrowing reduces the amount of money for private investment that's literally out of Mankiw's textbook.

And I think most a lot of people listening to what we're talking about now say, yeah, that's what I learned. That's true. And then also saying that a large amount of spending and a high level of government debt puts an unconscionable burden on future generations, which you'll also find in Mankiw and all the usual neoclassical textbooks. Now, from an accounting point of view, that is just wrong. Okay, I forgotten Paul Krugman's use your favorite way of putting it. But it is just simply a fallacy when you look at the accounting, and that's what MMT is based upon. It's saying let's look at the actual cash flows that are involved. Where does the money come from? And where does the money go to when the government borrows and what actually happens when a deficit is run?

Now, you read the economic textbooks, the deficit it takes loanable funds away from the private sector, and therefore reduces the rate of investment of the private sector and causes the economy to slow down while government spending boosts other parts of the economy. That's the way that the textbooks talk about it. But if you look at what actually is involved in banking, and of course, the last people you should ask about what banks do. A conventional economists, because I haven't got a bloody clue. They've lived with a set of models, the money, money multiplier, fractional reserve banking, and loanable funds, all of which are fallacies. And finally, I think I've said this numerous times. The Bank of England and the Bundesbank have both come out and said these are simply fallacies. That is not how banks operate.

In the banking sector, the point of view for the banks to is rather than banks lending out deposits, bank lending creates deposits. So that's a complete change in how we think about the private credit system, and what MMT is doing and there's complimentary to what I do in terms of analyzing credit. It is saying, well, let's do the same thing with looking at what the government does. So what happens when the government runs a deficit? Is it borrowing money from the private sector that the private sector would otherwise spend, which is what neoclassical economics teaches you? No it's not. When the government spends more than it taxes, it increases the amount of money in private bank accounts. To do that, it also has to increase the amount of money in bank accounts, private bank accounts at the Central Bank. So the act of putting money in your but your deposit account. If you got a, you know, a COVID check from the Biden administration or even the Trump administration when it existed. You know, a $600 check to you would be matched by a $600 increase in the reserves of the private banks that you bank with. otherwise, their assets and liabilities would be unbalanced. So that's simply accounting.

And when you look at that, you say, okay, the deficit has created money. So you use a private banking account holder, and the private banking system in general, you have more money in your bank account when the government runs a deficit. Now, how does the, how are those damn bonds bought? What happens with the bond buying? Well it just went through, because the increase in deposits of the banks caused by deficit spending is matched by an increase in the reserves of the banks, the private banks at the Central Bank by the same acts. Those private central private banks now have excess reserves, which normally earn no interest. So when the government, the Treasury then says we're going to issue bonds, or sell bonds to the private banking sector, to cover the size of the deficit, those bonds are purchased using the excess reserves created by the deficit. There's all sorts of timing issues involved and the government can be estimating ahead of schedule, what it expects to do and sell the bonds before it does the does the spending and so on, and yada yada yada.

But fundamentally, the deficit creates the money in the private bank accounts, and it creates the excess reserves that are used to purchase those bonds by the banking sector. So there is no problem. First of all, there's no problem about burdening future generations. In fact, you're enriching current ones, at least monetarily because they're going to have more money in the bank accounts. And the debt that is created, which is bonds is simply changing non income earning reserves for the banking sector, to income earning bonds for the banking sector. So all the scare stories that are a common part of saying I've got to control the deficit, etc, etc. are simply scare stories. They're not accurate as an accounting vision of a monetary economy.

Erik: Steve, you've emphasized very strongly over the years that the number one biggest problem we face is too much private debt. I wonder, obviously MMT, by its definition, involves more public debt because it's kind of what it is. It is a prescription of using public debt in order to accomplish public spending more effectively. It seems to me that there is an extension of that. That MMT policies really tend to also encourage more private borrowing and more private debt accumulation, which seems to me adds to the problems you're talking about. Would you disagree with that? Or is it just a question of needing to separate those? That teah, we do need MMT, we just need to be careful.

Steve: Yeah, I think we need to separate them because… this is, like MMT as they call it, Modern Monetary Theory. Because it's a modern development, you can trace it back to the 1990s. Initially, the Warren Mosley talking about how governments don't spend to tax. The tax to spend they spend to tax. And equally my work on credit is a modern innovation. I began during that in the 90s with my models of Minsky's financial instability hypothesis and I've only recently built a fairly general theoretical explanation for how credit adds to aggregate demand so there are two new elements. Now MMT from what I can see of what most of the authors have written MMT haven't yet got their heads around the role of credit properly.

Now, that doesn't apply to say Stephanie Kelton for example. As Stephanie's if you read between the lines in her book of deficit myth you can see awareness of the role of credit there but the focus is on government spending. But there was a debate, not a debate, a slanging match really, between Randy Wray and Doug, I think it's Henwood. Doug Henwood put out an attack on elements of MMT and as part of that, he said that the strange thing to him was that there's no role for credit in what he sees in MMT. And Randy Wray replies to it and said that, well, you know, overall, we regard he regarded the endogenous money revolution where people like myself developed an analysis of the role of credit, or how banks create money by lending rather than banks lending out deposits. He said, the impact of that was, quote on quote "trivial" because all it did was say that, rather than the government controlling the quantity of money it controls the price of money and the market sets the quantity.

Steve: That is incomplete, okay, when you have a new set of ideas like MMY on one hand and my analysis of credit on the other, it takes time for people to put them together. So I believe that they are compatible. And then when they are compatible, it means you have to worry about there being too much private debt. If MMT, you should be focusing on reducing the level of private debt, as well as saying there should be more feared money creation and less credit money creation. So it's possible to combine the two together, but that hasn't actually intellectually happened yet. I hope it will happen in the next couple of years. So they're not incompatible per se. They're not like Austrian vs. Post Keynesian economics or anything like that or Austrian versus Marxian heaven forbid, they're compatible but they haven't yet been combined.

Erik: Steve, when we've spoken in the past, at least in my perception, I would summarize what you've said is, look, we've got such a problem with private debt that if this goes too much farther, we're eventually going to get to the point where it's not just that maybe we might have to go to a debt Jubilee someday. But eventually, you get to the point where there's kind of a point of no return when there's no other option. Are we there yet? Or is this a zombie economy that is facing a debt Jubilee someday that's unavoidable? Or is there still a way to avoid that?

Steve: The way to avoid is by continuing being stupid and as Einstein used to say that the two things that are limitless, the universe and the human stupidity, he wasn't sure about the universe, but he was here about human stupidity. I've got to agree with him, I'm afraid on that front. But yes, I do think that we've reached a point of no return. Because, again, if I look just in terms of the history of America, and say, what's the level of private debt now versus its previous peaks? The current level of private debt again, courtesy of COVID is about 160% of GDP. It peaked at 170%, back in the financial crisis of 2009. The highest before that was 130% during the Great Depression, and then you go back to 70% in the 1910s. America is at its absolute ceiling in terms of its capacity to carry private debt given the other dynamics of the economy.

Other countries have had higher levels, but they're all carrying peak debt. Certainly in comparison to anytime since the end of the Second World War. So what that means is with so much private debt accumulated, the potential for any credit driven demand is minor. But as healthy capitalist economy does function better if you have credit demand, particularly if it goes to entrepreneurs, to enable innovation to take place. So you have something which is cutting off the potential for innovation, which is the thing which gives capitalism a reason to crow about itself as a social system versus any other. So we have so much private debt accumulated so much inability of both banks to extend further credit, and borrowers and individuals to take on that credit that you have credit stagnation.

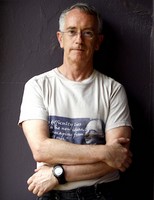

Steve Keen

And also, it means people spend the money they have in their pockets more slowly. You have a lower velocity of money because you want to hang on to the money you've got to pay the debt you've got. But by hanging on to the money, you don't spend it and therefore the turnover is lower, and you get very low bang for your buck out of the greenback in your pocket. So there's all sorts of reasons why we face permanent stagnation, unless we reduce the level of private debt and COVID has come through on top of that, and I think climate change will come on later. And just mean that unless you reduce the level of private debt, you're going to have mass bankruptcies.

Erik:

Steve, a few years ago, you wrote a book called "Can we Avoid Another Financial Crisis". And when we talked about that at the time, you know, I was thinking financial crisis! that means stock market crash. I'm starting to think the next financial crisis that the economy faces is more likely to be an inflation or runaway inflation, where, if anything, what you're worried about is an upside risk to the stock market, as opposed to a downside risk. And the risks that you get concerned with are not stock market crash, they're completely different. That probably is very much at odds with the deflationary conclusion that you at least in the past have drawn from this excessive overhang of debt. So how does this work? Do we need to be worried about a financial crisis that's more of like a crack up boom, or runaway inflation? Or is that not really in the cards?

Steve: I can't see runaway inflation just because I can't see runaway aggregate demand. And that's what you need to have a supply shock like we're getting coming through because of the COVID supply chain disruptions and mineral shortages as well coming out now. Like even hardwood in America, apparently, there's a shortage of that at the moment. But to have that turn into sustained inflation, you've got to have it being something that then leads to wage rises, which then lead back to more price increases and more wage rises, and so on. And you simply don't have the bargaining capacity in the working class in America anymore to enable that to happen. Nor do you have the credit based demand that used to exist, which could mean that the companies would absorb a price rise by borrowing, extending the lines of credit and their overdrafts and therefore keep the momentum going, or the price costs increase through the price system. So I can't see that happening.

What I can see is a massively overvalued stock markets courtesy of Federal Reserve intervention. And to me that's given you a fragility in the financial sector, which just basically requires good news to happen all the time to avoid a downturn. Now, of course, the Fed can dive back in and rescue those markets. Anytime it would like so long as those crises don't look like they're existential. But I overall just can't see a stagflation. I can see a stock market crash and the Fed diving back into rescue the markets again, which is what it's been doing ever since 2010. But it's not something I'd be trying to explain in the 1960s and 70s inflationary surge was.

Erik: Steve, I've been particularly looking forward to talking to you about ESG, environmental, societal, and corporate governance cognizant investing is the theme. Frankly, I don't think on one hand that I've ever heard a more valiant, more legitimate, more honorable concept, then for owners of capital to exercise their social responsibility to be responsible with it. So in principle, I love the idea. And I know is kind of a left leaning political guy. I've got to believe you like it, too. But you know what, I think ESG is a scam.

Erik: I think that most of what's going on is a bunch of Wall Street guys ripping off people who want to be responsible by selling them greenwash nonsense that has nothing to do with solving climate change and everything to do with separating rich people from their money. That's pretty cynical. You are a guy who follows this climate change stuff pretty darn carefully. Am I right to be that cynical about the way the investment industry has addressed this problem of climate change?

Steve: Yeah, absolutely. I mean, I'm involved with a group called the Biophysical Economics Institute that's trying to bring a bit of realism to ESG. And to tie it in to as well and to energy return on energy invested in point out the importance of that. And we want to have some validity coming out of the ESG. But fundamentally, anything like this is another reason for the wolves of Wall Street to start prowling Main Street. And that's how it's being bundled and packaged. Just like carbon offsets have, as if, you know, we can fix climate change by paying an extra 20 bucks on our airfare from New York to London. No, we can't. But it works out mostly for the companies marketing those offsets.

Erik: It certainly does. And you know, it's a much bigger scale than that. I've been reading these stories about people who were buying carbon offsets from people who didn't do anything. And the people that didn't do anything are polluting in a way that just doesn't happen to be being counted within that particular jurisdiction against them. Even though it should be and you know this ESG thing as far as I can tell, it is really mostly about Wall Street scamming investors into thinking that they're being responsible. The good news is investors want to go to sleep at night, feeling like they've been responsible and not just greedy with their money that's got to be an advance for society.

Unfortunately, Wall Street is in between those well meaning investors and actual do gooding and unfortunately I don't think that is going to change. How do we eventually get past this, Steve? Because you and I both, I think agree that climate is super important. We only got one planet, we got to take care of it. But frankly, I don't think that the people that are on the Crusades on either side are really dealing with the straight facts. I think this is a very politicized thing and the economics of it, I think, are making a mess in the investments that supposedly fix it, I don't think fix it. Are there investments that really do help or other things without going through ESG funds, that investors should be thinking about just how to be responsible investors and do good things with their money.

Steve: Even on that front, I mean, most investors are buying shares of other investors. You're driving up the price of the share, you're not giving any money to the company involved in whatever green technology you are allegedly supporting. So to me, I think we really need a wake up call about just how serious climate change is. Because I don't think it'd be done. I don't think it'd be handled by a profit-oriented private sector. I think the scale of this is so great that we're going to be forced to going backwards in size, the size of the economy, and firms are going to need cash support from a government to be able to stay solvent in the whole process.

And the one of the major reasons why we haven't taken it seriously is economists like William Nordhaus who have completely and utterly distorted the dangers we faced with climate change by the shoddiest work I have ever seen. I published a paper on that in the [inaudible] magazine, a journal called "Globalizations Last Year" on the title of it was "The Appallingly Bad Neoclassical Economics of Climate Change". Bottom line is anybody who's taking the numbers that economists have pumped out about what climate change means to the economy, are deluding themselves by an order of one or two magnitudes as to how serious climate change is going to be. So all they say is your stuff is just more greenwashing.

Erik:

Steve. I'm not going to let you pick on Nordhaus without substantiating your argument what specifically did Nordhaus get wrong that would cause you to make such a scathing statement on a public podcast on?

Steve: Two things in particular, like an overall orientation, which is just believing the climate change can't be bad because capitalism couldn't handle anything. Therefore climate change can't be too serious. And I'm not joking, that seems to be his mental processes. But in terms of trying to add up what the damage is to climate change will be, he assumed that 87% of American economy would be unaffected by climate change because it happens in what he called carefully controlled environments. Now, the industries he said, we're not going to be affected. We're all manufacturing, all services, all government activity, he even included overseas GDP. As part of everything he tried to expose the sectors of the American economy as unaffected by climate change. And that's become a common assumption for all the all the economists working in this field. That is basically saying the climate is weather. And so if you're not exposed to the weather, you're not exposed to climate change. That is nonsense. That is garbage.

The simple reason being and we can see this with a good example of Taiwan right now. One of the examples he gave of carefully controlled environment was microprocessor manufacturing. Why are we finding the micro processors becoming more expensive right now, it's because there's a climate change related drought in Taiwan that means like these enormous factories can't get enough water to do the processing. So the cost of microchip processes going through the roof as well as the disruptions from COVID. So literally mistaking climate for weather. And doing that in two ways. Also arguing and I've seen one of his fellow travelers on this front, a guy called Richard Tall make this argument that you can use as a proxy for what's going to happen to climate change, you can use the current relationship between income as I gross, that's the gross state product in America, and temperature.

So if you look at Maryland, for example, and find that Maryland is 10 degrees colder than Florida, and the Florida has got a 20% lower GDP than Maryland, therefore, you can say that a 10 degree increase in temperature would reduce the GDP of Maryland by 20%. Now, a 10 degree increase in global temperature would drive the human species extinct, period. And there's plenty of scientific papers to give reasons to believe that. The simplest one being for example, that one reason we have the temperate zone where most of the agriculture occurs these days, is because there are three circulation systems in each hemisphere. You have what's called the Hadley cell, which is the circulation of air between 0 and 30 degrees, from the equator to 30 degrees north. You then have 30 to 60 which is what they call as the temperate zone. And then you have the polar 60 to 90 degrees.

If we increase the global temperature by 10 degrees, which is seriously what was considered by one of his acolytes. That, according to two physicists, atmospheric physicists is twice the level of temperature increase that we put enough energy into the atmosphere to mean we went from three cells to one. It's like turning up the oven, the temperature on your stove on a bowl of soup, and you've got these little bubbles. They're called the early cells, circulating and you can see them increase the temperature and the whole thing bubbles and all the earlier structure breaks down. Imagine that happening and what happens to Western agriculture, what it would mean is all the rain would be occurring around the equator and around the pole. The pole would be 22 degrees Celsius in the middle, you'd have pretty much an extremely hot, drought stricken part of the planet. You simply can't use those assumptions to make up the data for climate change.

And that's what they've done to argue as Nordhaus does, that a six degree increase in temperature on the globe would reduce GDP very much by 8.1%. That is nonsense, absolute nonsense. And it only got through to be published because economists fundamentally are climate change deniers most of them. And they don't think you can criticize a theory because of its assumptions, which is crap methodology. So we have got nonsense numbers being used to give corporations the apparent guidance that there's only going to be a minor impact from climate change. It's all stuff economists have made out talking through their asses.

Erik: Well, I would say that that succinctly addresses my request that you clarify why you would make such a critical statements. Steve, let's move on from there. I gotta tell you, I really enjoy your perspective on economics, listening to you speak and also reading your books. It's been a few years, though, since I think it was 2017 that you published, Can we Avoid Another Financial Crisis". My Amazon is spying on you. I've got a secret message.

Steve: Oh, yeah.

Erik: It says there's a new one. It's called the new economics, a manifesto by Professor Steve Keen available for pre order but there's no look inside, so I can't see what's in there.

Steve: It's really saying that neoclassical economics is the phlogiston of the modern era. It's the Ptolemaic astronomy in the time of moonshots. It's a theory which is neat, plausible, and utterly wrong, which shapes how we think about how capitalism functions and is actually making capitalism dysfunctional. So we need a new economics that is not obsessed with equilibrium thinking. So we understand complex systems, that doesn't pretend that we're a barter economy, which have never existed in the first place. It's a monetary system, we have to look at money. And it's one way, energy is absolutely essential to production, whereas mainstream economics leaves energy out, it's thinking completely and imagined, you can have an economy with no energy input, which is total nonsense.

And all this has come out of the methodology, which ran into all sorts of problems, mathematical problems, where the various things that neoclassical would like to have concluded were proven to be mathematically false. And their answer was, let's make a simplifying assumption and jump over the problem. So for example, one of my favorite simplifying assumptions by Paul Samuelson to try to explain how you can take the theory of an individual having a downward sloping individual demand curve to get a market demand suppose sloping demand curve, he'd literally assumed that America is one big happy family. One big happy family that allocates income before trade so that everybody's happier the distribution of income before trade goes ahead. Well, literally, I've got that. That's what I quote in the book.

So we have a moribund failed paradigm still dominating how we think, and it's time we got a new one. And what I explained in that book is how you can have a new approach to economics based around complex systems, monetary analysis, and being realistic about the role of energy in enabling production to occur in the first place. And then of course, that ties up climate change as well. So it's a pretty heavy read. Mind you, I do use the word bullshit at one point inside the book, so not as heavy as you might think.

Erik: I can't imagine that coming from you Steve!

Steve: Of course not.

Erik: Of course not. Well, it is available for pre order right now on Amazon. So I am clicking as we speak. Steve, before I let you go, I want to bring our listeners up to speed. And frankly, it's a story I don't even understand completely myself. When I first met you, you were a university professor. That means guy gets up in the morning goes to a university, stands in front of a bunch of people in a room and gives a lecture. You changed all that. Basically, you were one of the first guys to call the 2008 financial crisis. Got kind of famous because of that. Got a big following.

Now you've kind of basically changed the rules to where you're still a professor of economics, but you don't work for university. You kind of do it freelance. How is that even possible? What's going on? And who are the students? Are we talking about student aged, you know, kids that want to learn economics from somebody other than a university? Are we talking about middle aged people who are investors? Who signs up to say, Steve Keen, I want you to be my my university-less professor?

Steve: Good question. It's an interesting combination, because it's all through Patreon. So without Patreon, I couldn't do what I'm doing now. And I've got about roughly 1500 subscribers on Patreon. And there are people paying everywhere from $1 a month, which we've been mainly with the student end of the spectrum to $1,000 a month. And if I look at the $1 end of the students. They are people who want an alternative perspective on what they're getting in the textbooks and what they're getting at university. So that's students getting an alternative education. I actually had a marvelous conversation, by the way, just to mention this, which is on my YouTube channel, where a group of school students got in touch and brilliantly informed group with a little website called Politics with Nick. And I had a conversation with these, even including a 13 year old who had his head around Sraffa, and all sorts of advanced critiques of mainstream economics that I didn't get my head around until I was in my 20s. So that's the student end of things.

And I think a lot of the others are people who would like to be doing what I'm doing, but are caught in jobs where they can't. So they're providing me with more than more than they need to give me to enable me to continue doing my work. So like most of the stuff, I've got up on Patreon, I make freely available. So you don't have to pay my Patreon to read what I'm writing there. And that was with the agreement with my patrons that I do it that way. But there are some things that I give to the people who pay the $1 and above. For example, I've given a copy of the manuscript of the new economics to all my subscribers, then there's a $10 a month podcast with a great mate of mine and great radio guy, Phil Dobbie as well. But I've got people paying 30, 100, 300, and $1,000. And they're not doing it because they have to, they're doing it because they want to.

And my interpretation there is that they would like to be doing what I'm doing. They can't manage to do it themselves because of their own commitments or their own industry. So helping me do it, is there a way of doing one for the team, and I completely and utterly applaud them and thank them for their support because without it, I'd be stuck back at home living on my retirement innings and, you know, scaling out what I could manage to do. With this work, I can be full time productive and it's been far far better than being stuck at a university where I've got to answer to bureaucrats all the time.

Erik: Now, if you want my prediction, the unexpected positive consequences of the COVID crisis is the whole world is going to change with more people like you abandoning the structures like universities and saying, Hey, I can do it all on the internet and I don't need all of that bureaucracy and all of that nonsense and I think that makes the world a better place. Steve, we're gonna have to leave it there in the interest of time. Patrick Ceresna and I will be back as MacroVoices continues right after this message from our sponsor.