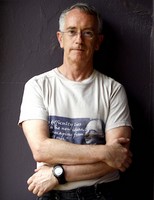

Erik: Joining me next is Professor Steve Keen who is both the author of Debunking Economics as well as the crowdfunded professor of economics on Patreon. Later on in this interview we’ll come back and tell you a little bit more about that.

Erik: Joining me next is Professor Steve Keen who is both the author of Debunking Economics as well as the crowdfunded professor of economics on Patreon. Later on in this interview we’ll come back and tell you a little bit more about that.

Steve, after our last interview I was left with my head spinning, as I always am, because you are just a firehose of fantastic information about economics, including those aspects of economics that deviate from the neoclassical school which all the big universities teach.

And I realized that it’s so unusual for me to disagree with you, but I left the last interview saying, wow, Steve is on the other side of a major argument which is, I’ve always felt that the US dollar, having the world’s reserve currency, although it may not benefit the entire world, certainly benefits the ability of the United States to fund its deficits. And there’s another argument which I think that you tend to favor, which is that it would actually be to the benefit of the United States if it would lose its reserve currency status of the US dollar.

So why don’t we start by you making that argument. How could losing reserve currency status possibly be to the benefit of the United States?

Steve: I’ll go back a bit and ask why did the US get the reserve status in the first place? And that’s because – I don’t know how graphic I can be with your audience – but it waggled its stick around at the Bretton Woods Agreement. Because the proposal on the table from Keynes for a post-Second-World-War monetary system was not to go back to the gold standard, which Keynes called a “barbarous relic,” but to introduce an international currency called the bancor which could be used for trade between different nations.

If Britain wanted to buy something off America, it would need to convert pounds into bancor, with the IMF acting as a sort of global central bank, transfer the bancor to America, and that would then be converted from bancor into dollars back in the USA.

The bancor would have been the international currency issued in proportion to the size of each country’s GDP. Of course America would have got the largest share of bancors at that stage. And the proposal was to use a system of semi-fixed exchange rates to reduce the scale of balance of payments differences between countries.

The objective was to have trade deficits of, I think, no greater than 2% of GDP and the same for surpluses. And the idea was the need to have bancor would be driven by trade and by financial flows.

If you’re running a trade deficit, you run out of bancors, they’d be forced to devalue. On the other side, if you’re running surplus, then there was a discouragement built in. First of all, you’d be taxed past the surplus of about 2% of GDP and then ultimately you’d be forced to stimulate your demand for imports.

So the idea was to use this international currency to reduce what Keynes saw as the deflating impact of countries running surpluses on global trade. He saw that as being one of the destabilizing factors of the pre-Second-World-War period.

Now, when it came to the actual Bretton Woods, a little bloke called Harry Dexter White represented the USA and he pretty much said, no, we won the Second World War. Therefore we want to take over from the pound as the reserve currency – completely overruling Keynes and all his proposals, removing all the controls that were built into the bancor structure to stop balance of payments imbalances becoming too extreme.

And, lo and behold, over time, first of all, America starts running large deficits, having run large surpluses, which is what Dexter White saw going on forever and was of course wrong. And then you had the floating exchange rate after de Gaulle’s attack on Nixon. And then you finally had the level of instability we have now where countries like China and Japan, Germany, Switzerland, Norway, and a few others are running trade surpluses of the order of 10% of GDP.

And America, of course, has used its power as the only country that can’t run out of American dollars to wave its financial stick over the planet. To me, this has all been – this level of chaos and confusion we wouldn’t have had if Keynes’s proposal had gone forward.

Erik: Steve, another point that a lot of people make is that, from the perspective of exports, it would be better if the United States were not the reserve currency, because export businesses would be able to export their product perhaps with a lower dollar and it would be cheaper for foreign buyers.

Please outline that argument and any other reasons that you can see that it might be to the benefit of at least some aspects of American business if the US dollar were no longer the reserve currency.

Steve: Absolutely. If you had a bancor system, which was Keynes’ idea of course, then the bancor’s relative ratio to other currencies would depend upon volumes of international trade growth in different economies. And if you buy bancor, you’ve got to buy them off the IMF. You couldn’t buy them off another country.

Since we’re using the dollar, every country has a demand for dollars, not just to buy American goods but to take part in international trade in general. So the demand for American dollars far exceeds the demand necessary for simple exports and imports. And that demand, of course, drives up the relative value in a floating exchange rate system, the relative value of the American dollar.

I haven’t done any empirical estimates of this myself, but I have seen claims that the American dollar is anywhere between 30 and 100% overvalued. In other words, it should be anywhere between 20% cheaper and 50% cheaper than it currently is.

And of course that would have meant, first of all, it would mean that American manufacturing now would be much more competitive than it is. Secondly, if you go back to the 1990s when America began to relocate production from the Midwest to China and turned the Midwest into the Rust Belt and China into the world’s industrial powerhouse, it was doing that to exploit enormous differences in wages between China’s workers and American workers.

Now the differences would still have been there, but they would have been half as large. And I think the level of relocation of production away from America to Third World export industrialization zones would have been far lower. So I think this is actually the deindustrialization of America.

Erik: Way back in the 1960s, Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, who at the time was the French finance minister (he went on to be the president of France), coined the phrase “exorbitant privilege.” In his description, the United States, he felt, had this exorbitant privilege, an unfair advantage which the US derived as a result of being the reserve currency issuer.

And what he described is, look, the US can effectively go into debt for free because there is so much artificial demand for US dollars from all the other countries around the world that the US can engage in deficit spending and run up just astronomical amounts of national debt. In other countries that are not the reserve issuer, all of that debt would eventually lead to much higher sovereign bond yields and higher cost of borrowing and all these other problems.

The US, according to d’Estaing, kind of got a free ride. And the result of that is that it has allowed the US to borrow and spend beyond its means without really paying any penalty for that. And it’s no surprise that we have politicians saying deficits don’t matter. Although I think deficits do matter in the end.

The reality of the situation is you can get away with deficit spending much more easily if you are the reserve currency issuer. And that’s exactly what the US has been doing, getting away with excessive deficit spending.

The other thing about this – and I think it’s really the same argument you just made but looked at from the opposite perspective – is that, for most countries, if you want to be able to import things from other nations because you want their goods and services, you’ve got to export the same amount of stuff in order to have a balance of trade.

Only the reserve currency issuer can get away with running a massive current account deficit, meaning we import all kinds of goods and services from around the world. We get their stuff, we don’t have to send any stuff back in return. We get to be the consumer of all of that stuff because there is so much demand for dollars.

Now I certainly understand – and this was d’Estaing’s point – for the rest of the world it seems like the US has an unfair advantage that’s not fair to everybody else. And I certainly understand that argument.

But from the perspective of the US, and the US government in particular, it seems to me that reserve currency status is what has allowed the United States to get away with all of this excessive deficit spending. We get away with running a massive, massive trade deficit, Steve, which nobody else could get away with.

We don’t have to balance our trade. We get to import all the good stuff. We export military hardware, which gives us a lot of political control over other countries. But in terms of building widgets and sending them to other countries, we don’t have to do that. So, it seems to me that, although it may be unfair to the rest of the world, the US really does have this unfair advantage that d’Estaing described.

And if we were to lose reserve currency status – and, by the way, I think that’s a very real risk – we’ll get into the petrodollar system in just a minute – but if Saudi Arabia is threatening to ditch the dollar for oil trade, we could lose reserve currency status awfully quickly and suddenly find that we can’t get away with financing our government spending the way we’re used to. And all of a sudden deficits matter and they matter a whole lot. And I think the US government would be in big, big trouble and be facing a dramatic increase in the cost of borrowing.

Am I missing something to think that loss of reserve currency status poses those risks to the US government?

Steve: I agree with about 70% of what you said, but I need to [go over] quite a bit of it. First of all, you’re focusing upon the risks of the government sector. And we want to backtrack and say, what actually is a reasonable level of the government deficit? What are the deficits that matter?

If you look at the world in terms of a functional view of how money is distributed, you have your private sector, which can borrow from the banking sector. You have your government. And you have your international system. So you have a private sector deficit, a government deficit, and a trade deficit. Those are your three possibilities. And the sum of all of them: What is a deficit for one is a surplus for the other.

So if you look at the world from government versus non-government, if the government is running a surplus, then the rest of the world is running a deficit. If you look at it terms of domestic versus foreign, if you’re running a deficit there is a matching surplus elsewhere in the world. So on and so forth.

Now, when I look at that in terms of what is a sustainable situation over time, if you have a growing economy and a growing money supply, and you have, say, the private sector wanting to save money – the private sector wants to have its expenditure being less than its income – it is going to have to be somehow getting more money in that it’s sending out. The only way that can happen, is if the reverse flow is happening for another part of the economy.

So if you’re going to have – the government is going to be running a surplus, the private sector runs a deficit. Is that sustainable? Where does the private sector cover its deficit from? It will cover it from the private banks. Which means that private deficit becomes an accumulate of private debt. Which can cause crises like we saw in 2008. It’s an unsustainable thing.

If the government is running a deficit, and therefore the private sector is running a surplus, how does it finance it? Ultimately any country issuing its own currency, and that of course includes America, has the capacity to produce that currency and finance its own debt using its own capacity to create its own money. So, on that front, it’s more sustainable for the government to run a deficit than it is for the private sector.

However, you then have the issue of what happens to your international sector. Now, what I’ve said so far is consistent with what’s called modern monetary theory. You’ve heard of MMT being discussed in modern debates. Where I differ from MMT is they under-rate the importance of the foreign sector. They think that it’s actually – exports are a cost and imports are a benefit.

I just completely reject that perspective. But what it leads them to saying – effectively, but they don’t actually say it explicitly – is, well, you should run a trade surplus. Because you’re sending out pieces of paper and you’re getting back goods and services.

Now, that, to me, I think comes out of what you’ve been speaking about, which is America’s capacity to do that because they have the reserve currency status. Any other country that tried that indefinitely would start to see its currency devalue. We’ve seen this happening with Turkey recently. You can’t run a persistent trade deficit as a country that’s not issuing the reserve currency.

America can get away with that. And I think that’s led to a lot of the excesses you’re talking about. But the main impact, I think, has been, firstly, the political power of the government sector, obviously.

But then also the financial power of the financial sector of America to purchase assets anywhere else in the world. And to become the global financial system – to become, fundamentally, the American financial system extended. Which I think has also been quite damaging to the global economy but quite strong privilege to the American financial sector.

Erik: Let’s take this theoretical and pull it into the practical. Because just last week Saudi Arabia has threatened this NOPEC bill which is before Congress, which would allow the United States to effectively sue Saudi Arabia of using antitrust laws in the United States and apply them to OPEC and say, you can’t have a cartel.

The threat is, basically, if you don’t drop this thing we’re going to drop the dollar as our pricing mechanism. Now, of course, the petrodollar system, which was really conceived just after the Nixon shock when we broke away from the original Bretton Woods Agreement that the US dollar would be backed and convertible into gold, the idea was, by pressuring Saudi Arabia to price its exports of oil in dollars, regardless of who they were selling it to, they essentially forced the international trade settlement currency to be dollars even though the Bretton Woods agreement was no longer being honored by the United States.

And the result of that, the whole idea of what the US was trying to accomplish with the petrodollar agreement, was to make sure that there continued to be this artificial demand for the US dollar and that it would continue to effectively be the world’s global reserve currency. If Saudi Arabia were to actually carry out this threat and ditch the dollar and start pricing all of their oil for export to other nations in something other than dollars – in euros or yuan or gold or who knows what – that would mean that the very large artificial demand for US dollars offshore would start to dry up.

And it seems to me – although I do very much appreciate your argument that, hey, if the US had not been given this license to recklessly borrow and spend for the last 60 years, we might be in better shape than we are today – but the reality, Steve, is we have got $21 trillion now.

If all of a sudden we lose this reserve currency status, there is no longer an artificial demand for US dollars anything close to what it is now because the petrodollar system, let’s say, were to suddenly collapse, doesn’t that create a fiscal crisis for the United States where suddenly we can’t fund our deficit spending and we’d look at potentially seeing US Treasury yields just go through the roof?

Steve: I don’t think the yields can go through the roof because the yields really are controlled by the Federal Reserve’s capacity to set that band for its own debt between its two target ranges. Because it’s basically the monopoly supplier and monopoly buyer, fundamentally, from the private sector of American dollars. So it can control the interest rates.

If you look at – again, just to put a bit of cold water on the whole idea that a currency collapse or crisis is going to lead to you having to have monumental interest rates because of all the government debt you’ve got – the biggest government debt in the world is owned by Japan. It’s about 2.5 times GDP. What’s the interest rate over there? Close to zero. It has been for 15 years. So forget interest rate link.

What you will see is a currency valuation link. So if you do have the American dollar not being replaced completely, but having a competitive system – not just the Saudis, but also I know Turkey is considering a similar thing with other Islamic neighbors. And so are Russia and China, and, to some extent, Europe are talking about something because they want to get away from all the outright abuses of that power that have become extreme in the hand of Trump.

So you have those three potential factors giving you an alternative means for international exchange not using the American dollar. If that happens, initially the dollar value is going to fall quite dramatically. And that would impinge upon the capacity to import from the rest of the world as easily as you’ve done. And yet, at the same time, you can’t replace that by domestic production because the manufacturing sector has been run down so significantly in the last 25 years that you don’t have the capacity to expand that production anymore.

So I can see it as giving America quite a severe jolt. But it won’t be something which causes interest rates to go sky-high. They will still be held in a band by the Federal Reserve. You might see rises in corporate rates and so on, but not large rises in the rates on American government debt.

Erik: Now, most of the products that you see at Walmart in the United States are imported from China. It seems to me that, if this were to occur and there was a marked devaluation of the US dollar versus other currencies, that would result in a massive inflation shock in the real economy in the US because we don’t have the manufacturing capacity to make widgets in the United States. That’s all gone offshore, to the detriment, perhaps, of the American worker. But we don’t have that capacity.

So if, all of a sudden, we have to pay much higher prices in dollars in order to generate the same price in yuan or yen or whatever for the imported goods, doesn’t that result in a really big inflation shock inside the US?

Steve: It can. Inflation shocks, you have to look at them in a proper empirical context. And most economists simply assume any currency devaluation will lead to an equivalent inflation spike in the country that is devaluing.

What actually happens quite frequently is firms will try to – first of all, you have long-term contracts determining prices that are often set out two to five years in advance, particularly for industrial goods. But mainly we have importers putting a markup on their imports for their profit level. They are willing to cut their markup to hang onto market share to some extent. So you don’t see a 100% pass-through of that sort of thing. You might see 30% pass-through.

So if you had a 10-15-20% devaluation in the economy in the American dollar, then you could see, yes, a 5 or 7 maybe – I wouldn’t say going beyond 10% – spike in the inflation rate. But, yes, you could see that spike occurring.

And it would also – obviously cramp the style of any Americans wanting to go on overseas holidays. So there would definitely be a decrease in the American living standards. And it would bring home to people, too, the extent to which you have been deindustrialized and relied upon this exorbitant privilege to get over it. If the exorbitant privilege goes, then you wear the full consequences of being deindustrialized in the last 25 years.

Erik: Steve, let’s come to the current risks that the US dollar faces in terms of maintaining its reserve currency status and talk about how real they are. Is this talk from Saudi Arabia just saber-rattling? Or are they really serious about ditching the dollar?

Likewise, we had another comment last week from, I believe it was a former undersecretary of the UN, calling for a global currency to replace the US dollar as the world’s reserve currency. Are these things really at risk of actually happening? Or is this just talk?

Steve: I think it’s at risk of happening. I don’t think the Saudis are going to go through with it though, because they’re incredibly intimately tied up with American military power and it would just be too dangerous for them to do that.

But I know China and Russia and, to some extent, Europe are talking about it because they are sick of the extent to which this is being used as a bullying tool by America. Particularly – just one recent example – the decision not to let Iran use the SWIFT system for international payments. That could never have happened if the American dollar wasn’t the reserve currency.

And you get American imposing its political will on the rest of the world using the fact that it’s the reserve currency. And of course that’s become intolerable under Trump. So I think the odds are, let’s say, one in three of a serious breakdown in that in the next 10 years.

But it could also be prevented. It’s one of these things – it doesn’t have the weight of financial numbers behind it like I could see with the credit crunch back in 2008 to say a crisis is inevitable.

But, certainly, there will be strains on the system and the American dominance can’t be guaranteed. And the more America now tries to assert that dominance, the more likely it is to encourage one of those alternatives to be developed.

Erik: Well, we certainly have this coming from a number of fronts. Russia and China have been talking about this de-dollarization campaign for years. Recently, they’ve got the European Union partially onboard looking for an alternative to SWIFT to prevent the United States from being able to impose sanctions on countries and on businesses which, at least in the eyes of the rest of the world, the US has no jurisdiction over.

As we think about how this might – let’s assume that there is significant pressure on the reserve currency status and that the – of course, this is not a binary thing, it’s not a switch that gets turned off one day. Let’s assume that the dollar is used less and less in coming years, both as a trade settlement currency and as a central bank reserve asset. Talk us through what the consequences of that would be for the United States, both government sector and private sector, as well as for the rest of the world.

Steve: Obviously, it’s going to mean a reduction in demand for American dollars on foreign exchange markets, which must mean a fall in the price over time. And it will be complicated by the usual spot and hedge markets and so on. But, yes, seeing a fall in the value of the dollar, unless America’s financial sector could no longer use the fact that it was American to have the power it has over financial institutions elsewhere in the world, so that the scale of the financial sector would be pulled back, your manufacturing sector would be more competitive.

But, as you know, you don’t have the industrial pattern you used to have. You’ve still got some outstanding corporations and outstanding technological capability. But you don’t have that machine tool background. The skilled workers that used to exist there aren’t there anymore.

So there would be a serious shock to America with more expensive goods to be imported from overseas and a slow shift towards having a local manufacturing capability, making up for the damage of the last 25 years.

I can see a lot of social conflict out of that as well, but a positive for the American working class, who really have been done over in the last quarter century. And that’s partly the reason why Trump has come about. And, ironically, Trump is part of the reason why this might come to an end, given how much he’s used his bombast and the American reserve currency status as a thug’s tool in foreign relations rather than an intelligent person’s tool.

Erik: Steve, I want to return to the subject of modern monetary theory, which you brought up a few minutes ago. This has become a very hot topic, and I think it’s going to be incredibly important in the political discussion going forward.

As I understand it, the basic essence of what MMT is about is that, for countries like the United States that have the luxury of being able to borrow in their own currency, the argument is made that, look, inflation is always a risk, but, if there is no inflation – which right now we don’t seem to have a really big inflation risk – there is really nothing wrong with the government monetizing a lot of social spending.

So we could have a universal basic income and a whole bunch of additional social benefits and we don’t have to raise taxes. We can just print the money, essentially, and it’s not going to hurt anything. Deficits don’t matter. It seems to me is the way I interpret this message.

And what surprised me is the whole thrust of your message for as long as I’ve known you has been, look, debt is the problem. Excessive debt is the problem. So I expected you to be an outspoken critic of MMT and say, no, more debt. It does matter. It’s no good. MMT is bad.

But I think you actually are somewhat of a supporter. So help me understand this. What am I missing?

Steve: You’re missing a division between the different types of debt. Let’s stick with the division of the domestic economy right now, just for a starting point, and we’ll bring in the international later.

If you have a financial system divided into three sectors: Let’s say a government sector, a household sector, and a firm sector. Let’s assume they’ve each got 100 million, billion, trillion, whatever dollars in their bank account and they turn it over twice a year. So I’m just working in hundreds – I want to give an arithmetic example of what MMT is about before we go into discussing its finer points.

If you have $100 sitting in each of those three sectors’ accounts, and each of them is spending $100 per year on the other – so the government is spending $100 on the household sector and $100 on the firms, and the firms are spending $100 on the households and $100 on the government, however the spending is caused. Your total expenditure is $600 per year. Your total income is $600 per year. They are necessarily identical to each other.

If you then have one of them saying I want to save money so, rather than spending $100 per year on the other two sectors, I’m going to spend $95 per year on the other two sectors. That particular year, this sector spends $190 but it gets $200 back from the other two sectors. It makes a saving of $10. Great.

Only, what happened to the other two sectors? Well, they previously had income of $200 and expenditure of $200. They have now got income of $195. Still their expenditures are $200. So they each have minus $5 of savings.

The sector that saved $10 is an expense to the other two that have now got minus $5 each. All you’ve done is redistribute who has the money. You haven’t created additional money because I’ve started with the idea that there is a fixed amount of money in the system.

The point I want to make out of that is that, if you are running a surplus in that situation, in your particular sector, the other two are necessarily running precisely the same deficit. The aggregate level of savings, in other words, is zero.

What adjusts when you do that sort of thing, what actually changes, is income. Previously you had an income of $600 per year. Now you’ve got an income of $590 per year. So the attempt to save at the level of one sector causes a fall in income at the aggregate level.

This is what Keynes called the fallacy of composition. We think it’s a good idea to save for ourselves. We, therefore think saving is a good idea at the national level. When everybody saves at the national level, because aggregate savings is zero, you get no savings. You get a fall in GDP precisely equal to the amount you are trying to save.

Now, that’s the intellectual framework I’m starting from. And it’s rock-solid because it’s simply looking at the accounting. What that means is, if you want to have a growing of GDP over time – 6.200, 6.10, 6.20, 6.30, 6.40 – either the money has to turn over more rapidly – and I’ll come back to that – or, the option I’ll consider first, somebody has to create that money.

Now you can create that money by yourself going into debt. If you’ve borrowed money from the private banking sector, you’ve got additional money, it also comes with additional debt. In net terms, you have zero gain.

If the government borrows money, it borrows the money from the central bank. Who owns the – I’m cutting down the steps in between, of course, because of course the central bankers, their Treasuries, are required to sell bonds to the private sector. Essentially, the central bank can buy those off the private sector, etc. I’m just going jump over that detail for now. But the government can actually continue running a deficit with its own central bank because it owns its own central bank. It can pay the interest bill using a call on the central bank etc.

What it means is the question comes down to does the private sector have the capacity to run a permanent deficit letting the government run a permanent surplus? The answer is no. Does the government have the capacity to run a permanent deficit allowing the private sector to run a permanent deficit? The answer is yes.

This is what has turned up in the empirical data.

If you think of the American government surplus over the last 120 years – and you’ll find this data at the White House – the surplus the government has run on average for the last 120 years is minus 2.4% of GDP. In other words, the standard deficit has been 2.4% of GDP. If you take out the wars, it’s still 2.2% of GDP.

So the standard situation, if the government runs a deficit and therefore the private sector runs a surplus, that is the sound foundational basis of MMT. It then says, well, which sector do you want to have maintaining a deficit? One of them has to. One or the other, the time is zero.

And the answer is, the choice is for the government to do it. But then the dangers become what if the government runs too big a deficit? Then you face the danger of either runaway inflation or runaway trade deficit.

Erik: So if the claim is that, during periods where we don’t have major inflation risk, it’s okay to have deficit spending, why wouldn’t the very first thing we do with this miracle power of MMT be to eliminate taxes during periods where there is no major inflation risk?

We know for certain that reducing taxes stimulates the economy. Why wouldn’t we start, before we worry about giving things away in universal basic income or something, by not taking money away from the people who earned it?

Steve: I’m actually a critic of income tax, so I’ve got to preface it with this remark. Because when you’ve got a perspective that the government can afford to run a permanent deficit, it inverts your understanding about the role of taxes.

At the moment, we think of taxes as being they define government spending. When you look at it from the point of view of saying, well, the government creates its own money, that creates its capacity to spend.

You then look at how big is government spending? Before the Great Depression and Second Word War, the government was about 5% of the GDP. This is even during the Civil War period. Now it’s 30%.

So if the government finances activities by simply printing money and not taxing it, it would be increasing the money supply by something in the order of 15-30% per annum. I think you’d get a pretty massive runaway inflation level with that. So taxation’s role is to take that money out.

And we’ve been doing income tax, I think, ever since the Great Depression. We relied upon Customs duties and stuff like that beforehand. I think it’s actually a very ineffective way of taking money out of circulation.

I would rather have a transactions tax system. And then fine-tune it to the extent to which you – I’m not saying it’s a way of financing government spending, but trying to stop too much money being pumped into the economy at any one time. And stop too much of that accumulating in one social class’s hand.

At the moment, without doubt, because of the capacity of the wealthy to evade their tax liabilities – whereas the middle class don’t have and the poor don’t have either the income or the ability to evade – you’ve got an enormous increase in inequality coming out of the income tax system. So I’d rather a changeover to a transactions-tax-based tax system.

And then you’d set it up so you get your gap between government spending and government taxation, not leading to an excessive creation of money.

Erik: Coming back to the subject of modern monetary theory and the risks or opportunities that are introduced, it sounds like you’re generally fairly open to the idea but still have some criticisms. So help our listeners understand, for the people who are trying to get their head around MMT.

Is it a good idea? Is it a bad idea? Should we take it seriously? Is it something that we should be looking at as a philosophy for how we run governments? What are the ups and downs that they need to understand?

Steve: I’ll put out two little points. One little point where I disagree with MMT – so that’s off the table straight away – and that is that I disagree with their perspective on international trade. They start from a very different basis for international trade, talking about exports being a cost, imports being a benefit, arguing in favor of – not explicitly saying it, but ending up saying that running a trade deficit is a good idea. I disagree with that.

But on the domestic money analysis, I think they’re spot on. And what it means is you turn upside down your understanding of the government role. The government doesn’t need to tax in order to spend. It spends and then taxes to take excess money out of circulation. That means, in that sense, that it’s not constrained by a hard budget constraint, which most of us are constrained by.

If, as non-government individuals and companies, you are permanently running expenditure greater than income, you are going to be forced to cut back because you’re going to run out of dollars. That can’t happen to the American government. It can’t run out of dollars. So that means it’s liberated from those constraints.

And then the question is, well, what are the main constraints upon it? It ends up being the practical constraints of that particular economy: Your physical capabilities, the resources you have, the infrastructure you have, the people you have. If they are unemployed, or if you have a lower level of innovation than you would like, etc., you can use the government’s financial capacity to create that.

We saw that, classically, for America during the Apollo period when just the decision to compete with the Russians of getting the first human being on the moon meant an enormous amount of money being spent in fundamental research into rocket science – which we have ultimately benefited from, far more so than we have benefited from war. There have been no negative side effects.

If the government creates that spending, it can finance the universal basic income, as you said. It can finance university education; you don’t need to charge student fees. I would rather actually have the government create money by giving money to students to spend than giving it to bureaucrats to spend.

It gives you a creative freedom for an economy whose resources are not fully employed. And it means you stimulate Main Street, if you like, directly, rather than stimulating Wall Street, which is what we’ve done by the current economic philosophy which comes out of neoclassical economics rather than MMT.

Erik: But, Steve, it still seems to me when I look at the way politicians are latching on to MMT, they want to use it as a license to just spend, spend, spend on everything they can think of in order to give constituents every possible free giveaway in order to buy votes.

It seems to me that that has to ultimately lead to a massive increase in indebtedness. And I know that you’ve said before that excessive debt has been the whole problem. So how do I reconcile these ideas?

Steve: Think back again to the nature of that. Pork-barreling is as American as apple pie. I don’t need to tell you that. Who is the member for Boeing these days? Obviously they’re going to have a lot of work on his or her hands right now with the 737 MAX story. But you’ve had corporations effectively buying American politicians for decades.

So you’ve got the pork-barreling thing. The think is, when you believe there is a restraint on government spending caused by needing to tax before you can spend, then you have a limit on that pork-barreling.

And a lot of people who know that the practical finances are the other way around – this includes, for example, Paul Samuelson, since deceased. He was aware of this. He said we tell a porky fundamentally about the government’s funding because that way we stop the politicians excessively pork-barreling.

So it was seen as a way – even those who knew that the description of before you can spend was wrong, they thought that was a way of stopping the politicians getting their fingers too deeply into the trough.

Now, when you look at the issue, yes, you’re going to run government debt doing that. The question comes back to what type of debt are we talking about? Where does the government have to borrow the money from?

If the government had to borrow the money from private financial corporations and pay them interest on it, etc. in a currency it didn’t produce itself, it would be in serious problems. But it fundamentally sells bonds to the financial sector. The central bank can buy all those bonds back off the financial sector anyway. And then, when the bonds are paid, the interest is paid by, effectively, the Treasury telling the central bank to credit the accounts of people who got those bonds.

So the funding issues for a government are much, much simpler than the funding issues for a private entity. So, when I worry about the level of debt, I’m fundamentally concerned about the level of private debt. That’s what’s ignored, just to give your listeners a bit of a picture on that.

I think the current level of government debt is about 110% of GDP in America, maybe a bit less. The current level of private non-financial sector debt, just the debt of the non-financial corporations and households to the financial sector, is 1.5 times GDP. And it was 170% back when the financial crisis peaked.

So, to me, it’s the private debt that matters. The government debt is effectively like government equity in your economy. Because, again, a government can’t go bankrupt in its own currency. It can run out of another currency if it needs it. That’s Argentina’s problem. Venezuela’s as well, quite probably. But America can’t run out of American dollars.

So the worries about not being able to pay your debt as a government, not having enough of the currency to spend to cover your debts, it doesn’t apply for a national government. But it does apply for individuals and for corporations.

Erik: Steve, before we close, I want to move on to another topic which I know is very much near and dear to your heart. And that is the role of economics in the university system and how well the university system is doing in terms of being true to reality with its teachings.

You are a guy who has an amazing track record. You, with astonishing accuracy, predicted the 2008 crisis before it happened. You laid out what was going to happen, why it was going to happen, and how it was going to happen. You would think a guy with that kind of track record would be teaching at the very best Ivy League universities. You seem to want nothing to do with Ivy League universities because you don’t believe what they’re teaching.

When I first met you, you were associated with not an Ivy League university but a very well-known university in London. And I know that, since our last interview, you’ve left that university and I believe that was out of some frustration with the whole system.

And you’ve now gone on to basically being professor at large, teaching economics to those who are interested in learning what you have to say. And you’re funded through Patreon.

How is a guy with your track record either unwanted by the university system? Or what has happened to the university system that you don’t want to be part of it that has led you to basically being a freelance professor? This is a very unusual situation.

Steve: I’m afraid I’ve got so used to it that I take it as the norm. But, you’re right. It is crazy. In any other discipline, if you had somebody who predicted a serious earthquake before it happened or somebody who warned of serious storms or somebody who stopped a plane from crashing, or warned it was going to crash, yeah, you’d be in demand at the leading universities.

But in economics there’s an ideology that dominates. We call it neoclassical economics. It began in the 1870s. It had a legitimate reason for its development back at that stage. But it’s basically proved itself completely wrong, internally inconsistent. But it’s continued on because, once people believe something, it’s very hard to get them to stop believing it.

And, therefore, neoclassical economics sails on, despite the fact that neoclassical economists predicted 2008 were going to be a fantastic year. A bet-the-house year. It was going to be a burning economy. And they had no idea this crisis was coming.

Yet the consequence for the economists who believed that and got it wrong has been they’ve continued having the same old jobs at the same old universities. Because the economy continues to operate even if economists are wrong about how it functions.

But if engineers were wrong about how planes flew, they’d all crash. So the consequences for an economist of being wrong are nothing like consequences for an engineer. And, therefore, you can continue reproducing a false ideology indefinitely.

That’s what’s happened in the universities. And because they dominate the journals and dominate the selection systems, dominate the government funding bodies as well, they are the ones who decide who gets to teach at which universities.

As a result of that, people like myself who are non-mainstream and criticize them can’t get jobs at the top universities. We can only get them at lowly ranked ones like Kingston or University of Western Sydney, which I used to be at beforehand. They are the ones which put on the non-orthodox programs. But the people like Gregory Mankiw and so on dominate programs like Harvard.

Erik: Well, Steve, at least this dark cloud has a silver lining to it. We have a lot of listeners who might really enjoy learning a lot more about economics because they’re so interested in it as investors. Unfortunately, as much as many of them would like to go back and get a degree in it, they don’t have time to go back to university. They’ve got lives to lead and careers to work in.

You have moved on from the university system. You’re now offering a formal education. You’re a very experienced professor who’s worked in the university system and you’ve effectively become professor at large, offering an economic education to anyone who wants it. And you’re not focused on neoclassical economics. So please tell our audience: What you do you focus on? And where they can learn more about it? And how much does it cost?

Steve: It basically costs a minimum of $1 a month and as much as you want to give above that to support me on Patreon. The URL is www.patreon.com/ProfSteveKeen.

And I now have about 1,100 supporters there who are giving me something close to about $8,000 a month in return for getting access to my regular blogs on that particular site, to my books Debunking Economics and Can We Avoid Another Financial Crisis? and anything else I’m producing as well.

It’s not a formal education system as yet, but it is an exposure to my non-orthodox ways of looking at the economy which includes having a monetary approach. Remember, on that basis I built a software package I called Minsky for doing monetary non-equilibrium modelling. And all the insights of that turn up on my Patreon page.

I’ve also started doing work recently on the role of energy in production, which has been completely neglected by all schools of economics, not just the neoclassicals. I’m now doing that work with Tim Garrett who is a leading atmospheric physicist.

It’s an exposure to pretty much an engineering-based monetary non-equilibrium vision of economics through my Patreon page. And, over time, I hope I’ll finally get to that formal education component as well. But in the meantime, I think the best place to learn economics is outside the university sector.

Erik: It’s a sad statement about the university system, but definitely an opportunity for our listeners. Because I certainly think that you have the clearest and most concise explanations of how things really work in the real world. So, folks, I encourage you to check out.

We’re going to have to leave it there in the interest of time. Patrick Ceresna and I will be back as MacroVoices continues, right here at macrovoices.com.